What does it take to be a successful researcher? No doubt ability, determination and a certain amount of luck. But what else? It is easy for those already at the top to opine liberally, but their views are sometimes dismissed by those coming up behind them as out of touch with current realities at the coalface. Times Higher Education decided to directly canvass the views of those deemed to be the research leaders of the future.

The 420 respondents to the THE-Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings Research Success Survey are all members of the Lindau organisation’s alumni network. That is, they have been selected to attend one of its prestigious annual conferences, which are held for under-35s in the fields in which Nobel prizes are awarded: physiology or medicine, chemistry, physics and economics.

This demographic is reflected in the profile of the respondents to the survey, carried out in June and July: the majority (64 per cent) are under 34 years of age, with a quarter (24 per cent) under 30. Just 14 per cent are over 40. It is also reflected in respondents’ contractual status, with most in junior positions and 57 per cent on fixed-term contracts; only 30 per cent are in unequivocally permanent positions.

Lindau’s German base is reflected in the fact that 224 of the 420 respondents are in Europe and 97 in Germany itself. However, Asia (84) and North America (73) also have good representation. Africa has 24 respondents. Other continents are excluded from our analysis owing to lower response rates.

Most respondents – 79 per cent – are in academia. Of those, a third are in postdoctoral positions and a quarter are PhD students. A full 42 per cent are chemists, while 21 per cent are physicists, 19 per cent are biologists and 7 per cent are economists.

Meritocracy

One question often pondered about research success is how much a privileged background confers an advantage. Asked to rate their family backgrounds on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 is poor and 5 is rich, 68 per cent rate themselves 3 or higher. However, most (44 per cent) opt for 3, and only 3 per cent rate their backgrounds rich, against 6 per cent who rate it poor.

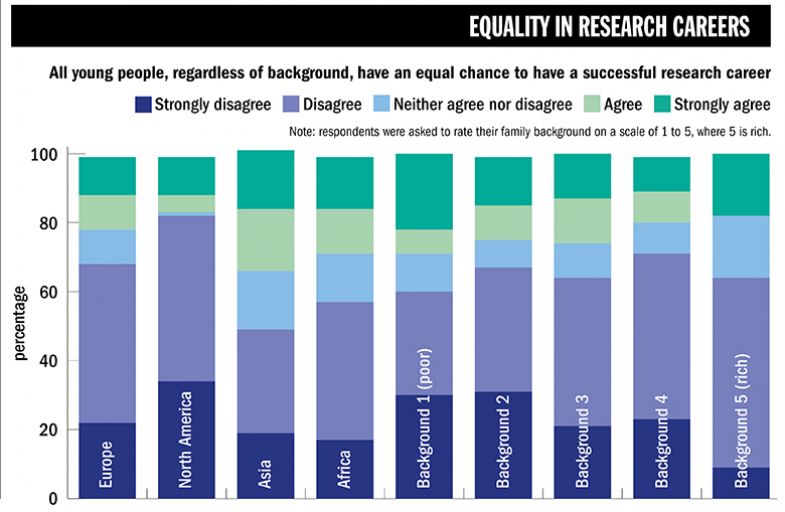

Asked whether all young people have an equal chance to have a successful research career, 66 per cent disagree, 24 per cent strongly. Only 24 per cent agree, 13 per cent strongly. Agreement is strongest in Asia and weakest in North America, where just 16 per cent agree. Strikingly, agreement is slightly higher among those who rate their backgrounds as rich or poor, rather than somewhere in the middle.

Many respondents make the point that equality of opportunity is very country-dependent. “I’d say the chances [of research success] are almost equal in my home country (Finland) but not in all the countries I’ve worked in or collaborated with,” says a postdoc in Finland, who grew up in “a small countryside village without much exposure to university people”. She also notes that of her parents, one was unemployed and another lacked a credit score – but one had an MSc.

Several respondents say that having parents specifically from an academic background is advantageous. A Germany-based PhD student sees success as “so much dependent on behaving in the way that is expected by those already in higher-up positions in academia”. Meanwhile, family wealth means “you will be able to afford a better education. I’d love for [access] to be equal, but it just isn’t.”

Not everyone sees childhood disadvantage as a problem, however. A chemistry assistant professor in Italy says that, unlike her school classmates, she did not have any tutoring help from her (non-graduate) parents. “However, this made me even stronger!”

Several respondents make the point that it isn’t so much early life background as early career background that preordains success. “If a young person is not a strongly motivated research machine or simply a genius, their research career depends on the research group(s) they join,” says a chemist in the Russian private sector. Meanwhile, a chemistry assistant professor in Cameroon says that “working in certain African institutes, with limited access to facilities, conditions the data you can collect and therefore the journals in which you are able to publish”.

And then there is politics. “Nowadays, academia is compromised with nepotism and favouritism. That is reflected in paper publishing, as well as academic position,” says a postdoc in India.

Asked specifically whether “universities and research institutes typically appoint and promote the most qualified candidates”, opinion is split, with 38 per cent agreeing, 31 per cent disagreeing and 31 per cent having no firm view.

However, those who disagree are more vocal. “Universities will often hire the candidate with the most fashionable research or the candidate they know. I have seen excellent candidates turned away again and again for below-par candidates,” says a private-sector chemist in Ireland. And an associate professor of chemistry in Ghana adds that some “average students” are sometimes hired on the basis of their “work ethic and consistency”.

A postdoc in Switzerland questions the definition of “qualified”: “Qualification for being a successful active researcher is very different from [that for] being a successful mentor and leader. This is not at all taken into consideration,” she says.

Bias is also cited by several respondents. “Institutes often prefer candidates from a certain background, institute, and even gender,” says a chemistry postdoc in the Netherlands. And in the experience of a public-sector physicist in Germany, “if you want to succeed in the European Union and are coming from a non-EU country, you need to perform much better than your peers from EU countries.”

If equality of opportunity is often an illusion, should researchers from underrepresented groups be preferentially recruited by universities and research organisations? Overall, 40 per cent of respondents agree, against 23 per cent who disagree. Perhaps unsurprisingly, agreement is stronger among women (44 per cent); more surprisingly, it is highest (55 per cent) among respondents from the richest backgrounds.

But many respondents are wary of outright positive discrimination, fearing it may dilute quality. Institutions “should go out of their way to advertise positions to researchers from underrepresented groups and invite them to apply. They don’t need to guarantee a spot for them, but having a more diverse applicant pool is the first step,” says a female postdoctoral chemist in Canada's private sector.

“No hiring panel should be complete without a quota of diverse underrepresented groups, and they shouldn’t close the role until they have at least one application from a highly qualified underrepresented candidate,” adds the chemist in Ireland. “Giving them a seat at the table will naturally lead to more recruitment.”

Others are adamantly opposed to positive discrimination. “I fundamentally disagree with identity-based recruiting,” says a male research fellow in Germany. “My only hiring criterion is: ‘Can this person accomplish the research task, and go beyond the call of duty?’"

One question about diversity is whether it is purely a question of justice, or whether it is also related to academic quality. Asked whether the involvement of people from a range of backgrounds improves the quality of research, 90 per cent of respondents agree, 49 per cent strongly. Agreement is strongest among women, biologists and people from poorer backgrounds.

“Different ways of thinking improve science, and different backgrounds may connect to some level with different thinking,” says the postdoc in Finland, a physicist.

“If you only come from the dominant class then you have not had as many challenges along the way [and] may not have been forced to think in a way that runs contrary to popular thought,” adds a chemistry PhD student in Germany.

The chemistry postdoc in the Netherlands says that while the point of diversity and inclusion “is more a matter of justice and humanity than of its effects on productivity”, it is also true that “understanding our biases and our political role as scientists gives us awareness of our own limits of interpretation. So, in that sense, it can indirectly improve quality too.”

A chemistry postdoc in Germany agrees that “diversity of background should translate into higher creativity inside a research group, ability to appreciate different points of view and gathering people of complementary skills. However, the management of a highly diverse team tends to be more challenging because not all members are equally likely to follow the same management tools and strategies.”

Other respondents assert that it is diversity of scientific background, rather than identity or socioeconomic background, that improves quality.

Another source of potential prejudice is institutional reputation. Asked whether they believe that this affects the way research is judged by journals, grant panels and others, 90 per cent of respondents agree, 44 per cent strongly. The view is much stronger in North America than in Asia or Africa; it also appears to be stronger among more senior ranks, although postdocs also hold the view strongly.

A “known name” offers “some comfort for the reviewer”, says a Germany-based PhD student in chemistry. “I don’t see how this can be changed without grants becoming completely blind to who applies.”

Meanwhile, a Canada-based postdoc says that in chemistry “corresponding author names appear to be more important” when it comes to securing a good hearing with review panels.

Others see national biases at play. “I am absolutely sure that a paper from Portugal or Brazil will end up in a lower impact factor journal. But the same work from a top university or other country will have a higher probability of ending in a better journal,” says a research fellow in Portugal. And a Chile-based postdoc has “reviewed and rejected articles from ‘good universities/research groups’ due to bad data and seen them later published in that same journal”. Even a Denmark-based postdoc has sometimes felt the need to “find additional American co-authors just to increase our publication chances, especially in American journals”.

A Netherlands-based chemistry postdoc says it “makes sense that committees look at institutional reputation. But often this is used as an automatic validation stamp when it should be looked at together with effective output”.

But if institutional bias is rife, does that affect researchers’ choice of institutions? For two-thirds of respondents, the answer is yes – and 17 per cent strongly agree that institutional reputation influenced their choice of their current or most recent university or research institute. Only 18 per cent disagree. Interestingly, although Asia-based scientists are more sceptical of the role of institutional reputation in scientific success, they are marginally more likely to agree that it played a role in their choice of institution.

“Reputation dictates visibility, and visibility dictates funding opportunities, and funding opportunities dictate survival,” says a Germany-based research fellow in chemistry.

Other respondents cite the relationship between reputation and top-quality students and facilities. But the Denmark-based postdoc, a biologist, was more attracted by his PI’s reputation, while the associate professor in Ghana rejected highly rated foreign institutions, choosing instead to “work in my home country due to the strong desire to be part of the critical mass needed to train the next generation of researchers to effect social change”.

If institutional and other biases can affect referees, is peer review the fairest system to allocate journal space and grants? Just under 45 per cent of respondents agree that it is, although only 6 per cent strongly, while 24 per cent disagree. Agreement is slightly lower among women, and much higher among professors (62 per cent).

“If reviewers were trying to fairly judge grants and papers, it would be a good system, but too often personal feuds get in the way,” says a Germany-based research fellow in chemistry.

But few respondents have concrete suggestions for an alternative to peer review, and many express variations of the view that it is the worst system apart from all the alternatives. However, double-blind reviewing is commonly cited as a way to improve fairness, while a Sweden-based PhD student suggests that “publishing peer reviews (even if they still are anonymous) might also improve civility” – as might reducing job precarity, so that “scientists feel less need to sabotage others competing for survival within the system”.

An Italy-based assistant professor suggests enlisting experts in the general topic area from outside academia “to avoid evaluation bias due to peer reviewers being in competition with the principal investigator”.

The Finland-based postdoc cites the increasingly common idea of using peer review merely for an initial sift of grants, with final decisions made by lottery – particularly at early career level. “This would save everybody’s time (since not every word would have to be polished or evaluated), reduce reviewers’ anxiety about having to invent reasons for turning down good candidates, and support the self-confidence of the young candidates when they do not have to read those half-invented complaints,” she says.

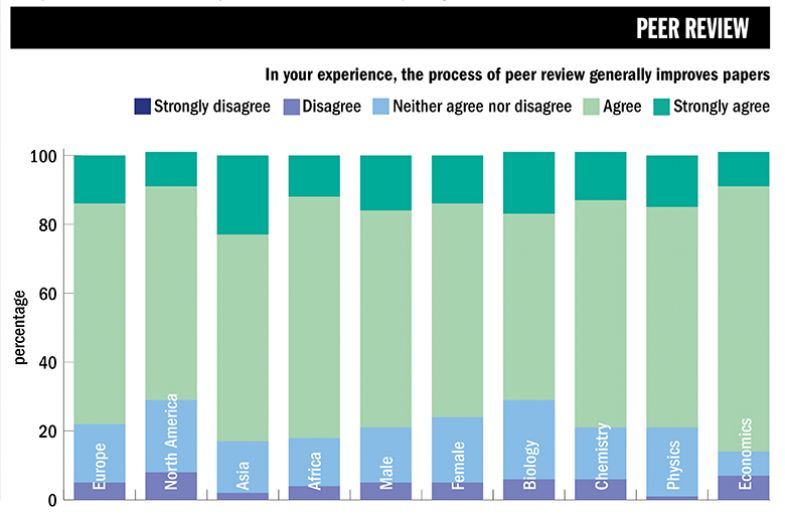

For all the cynicism about peer review, however, 77 per cent of respondents agree that, in their experience, it generally improves papers – 15 per cent strongly – and only 5 per cent disagree. But responses vary widely, with agreement highest among men, those with permanent positions and physicists. It is particularly low in North America and particularly high in Asia.

“People put a lot of work into peer review and even though we don’t always want to hear the comments, they are usually right and improve papers,” says a Netherlands-based assistant professor in chemistry.

But several cite bad experiences with “the occasional ‘Reviewer 2’, who undeservingly forces a paper to go to a journal with less impact”, as an Austria-based assistant professor puts it.

A US-based biology postdoc also complains about the burdens imposed on authors by reviewers. “The overwhelming amount of additional experiments that is increasingly being asked for by reviewers will, of course, improve the paper. The question remains: what are the costs of such lengthy (in my field, easily more than one year) revisions on scientific progress and the careers of young scientists?”

Institutional factors

What about the institutional factors relevant to research success?

Mentoring is one consideration that has come increasingly to the fore, and its role is appreciated by our respondents. Asked whether they agree that mentoring is an important factor for research success, a full 96 per cent agree, 61 per cent strongly.

“So much of research success, especially in academia, has to do with unspoken, unwritten, untaught norms, rules and standards,” says the Canada-based private-sector chemist. “How to choose a good research question, how to conduct important and good research, how to communicate results and participate in the community: a good mentor will pass [answers] along to their students.”

A Netherlands-based chemistry postdoc agrees: “Without mentoring, you basically have to want it a lot and make your [own] way to figure out how things are supposed to work. That alone costs so much energy that it makes innovative research more challenging. The mentor will put you in places you didn’t realise you could be at. Without good mentoring, only the over-confident make it.”

But is the mentoring provided adequate? Only 56 per cent agree that in their most recent academic position, they have had the level of mentoring they need to be successful. Nearly a quarter (24 per cent) disagree. Agreement is highest in Africa, among males and in chemistry. It is weakest in Europe and in physics.

Several respondents note that although they have had good mentoring, attaining it required their own initiative. “I am vocal about the training and guidance I need. Others without this trait have not succeeded in this lab environment,” says a US-based postdoc in biology.

A common barrier to research success is perceived to be parenthood. So do academic institutions “support pursuing an academic career while having obligations related to family/childcare”? Only 25 per cent of respondents agree, 6 per cent strongly, while 43 per cent disagree, 11 per cent strongly.

Agreement is weakest in North America, where just 14 per cent agree. Agreement is much stronger among men (30 per cent) than women (18 per cent).

In some countries, policies on parental leave are thin to non-existent. For instance, a Mexico-based PhD student says “the state does not offer childcare services, nor permit maternity. You have to take leave so that you can attend your maternity period, but without pay.”

A government scientist in the US laments that parental leave is not mandated by federal law there either: “An employer is considered ‘generous’ here because they give six weeks of paid leave. Such a stressful work environment negatively and directly impacts young researchers in their reproductive years.”

But even where more generous policies are in place, problems exist. In India, “academic institutes only grant six months of maternity leave”, says a postdoc there. Beyond that period, “the support of colleagues is key”. A PhD student in Sweden adds that “since many evaluation metrics, such as the h-index, are cumulative measures of quantity rather than quality, many people having young families fall behind”.

Many respondents point the finger at a culture of overwork. And when asked specifically whether such a culture in their field “negatively affects work-life balance”, 82 per cent agree, 35 per cent strongly. Only 4 per cent disagree. Women are more likely (86 per cent) than men (78 per cent) to agree, while economists (72 per cent) are significantly less likely to agree. Agreement is strongest in North America, where 92 per cent agree, and weakest in Europe (77 per cent).

Several respondents note that ingrained habits of overwork persist even when they are not being externally enforced. “In my work environment, overwork is not stimulated by the boss and is not appreciated by many colleagues,” says a Germany-based research fellow. “However, the tendency to overwork correlates to the employee’s background. Europeans are less inclined to do it, Americans (both North and South) are more prone to it and Asians are much more prone to it.”

A male biology postdoc, also in Germany, asserts that “overwork is personal choice, not a culture”. And it is a choice that many make. As the private-sector chemist in Germany puts it, “If you want to succeed, you need to force yourself to work more than the others. There’s no other way unless you’re in a place where you can benefit from nepotism or some privileges. And in such places you’ll never thrive.”

But principal investigators can certainly push their charges to choose work over other pursuits. “‘Academic research is not a 9-to-5 job’ is something I never fail to mention to my juniors,” says a male, Germany-based research fellow in chemistry. And the Denmark-based postdoc’s former PI in Germany “saw work-life balance and vacations as personal attacks on him. We had a master’s student [die by] suicide and [more than half] of PhDs dropping out without finishing…A friend was refused any vacation for 18 months (even for a funeral) until he quit.”

Leaders, of course, are often only projecting the standards they apply to themselves. A female, US-based administrator concedes that “expectations in my role must be managed in order to maintain a healthy work-life balance. It is a constant struggle. However, part of the public role I signed up for includes giving up some work-life balance.”

The research fellow in Portugal, a woman, does not regard research as work and “will happily do it on Sundays, evenings, etc. On the other hand, I try to have a good work-life balance and I also have other activities because it actually helps me focus on research.” And an assistant professor in Singapore warns that faculty must learn to “protect themselves” from their intrinsic motivation to overwork. “Better institutions do attempt to instil this in their new hires,” she says.

But do institutions offer enough help to new hires – or old ones? Asked whether they do “everything they reasonably can to support academic careers”, just 18 per cent of respondents agree, and only 2 per cent strongly. This compares with 51 per cent who disagree, 12 per cent strongly. Agreement is highest in Asia and Africa; while men (21 per cent) are more likely than women (15 per cent) to agree.

Many respondents make the point that support varies widely by institution and by country. “I agree that universities and research institutes do everything within their capacity. But the capacity strongly depends on national budgets,” says a male, Germany-based postdoc. And in the experience of a research fellow, also in Germany, “the administrators tried, but every layer of support comes with an extra layer of paperwork/bureaucracy that deters scientists from [accessing it].”

But the public-sector biologist in Germany is less sanguine about motives: “Universities kick you out once your grant is expired. Permanent positions are unicorns. Every university that claims something else is committing fraud.” And a postdoc in Austria says: “Universities and research institutes are interested in cheap labour. Careers of individual research are more of a hindrance to them.”

A postdoc in Switzerland says universities “do not have enough feedback mechanisms in place to protect young researchers against abusive PIs: this causes an efflux of promising scholars. At mid-career levels there are not enough permanent non-PI positions, and there are few options for dual careers.”

Meanwhile, the US administrator is “not sure US universities do a good job of balancing required teaching loads, research expectations and service requirements for faculty”.

Asked whether university academics should be required to be both good researchers and good teachers, however, more than two-thirds of respondents – 69 per cent – agree, 26 per cent strongly, compared with only 19 per cent who disagree. Agreement rises to 78 per cent in Africa and falls to 63 per cent in North America.

“To be a role model, one has to be good at teaching and research. Good research propagates good teaching methods and offers new grounds of knowledge,” says a private-sector biologist in Kenya.

Among disciplines, belief in the need for excellence in both teaching and research is highest among economists (83 per cent) and lowest among biologists (62 per cent).

“Someone who is only a good researcher should leave to industry,” says a German public-sector biologist, while the public-sector chemist in Ireland says academics must be good managers, too. “There should be mandatory training, with mandatory refresher courses every two or three years,” she says. “It is shocking we allow academics to hire and be in charge of young researchers’ careers but never ask how they plan to manage a team, support career growth and enhance their teams’ skills.”

But many respondents emphasise that excelling at both teaching and research may be unrealistic. “The qualities for both activities are not the same, or necessarily complementary. I believe in splitting the academic career into positions for teachers (based on pedagogic merit mostly) and researchers (based on scientific merit),” says a postdoctoral chemist in Portugal.

The difficulty of excelling in both teaching and research has a potential impact on the quality of both. Only 15 per cent of respondents believe that the teaching currently being delivered in their field is the best it could possibly be, compared with 54 per cent who disagree. Agreement falls to 9 per cent among biologists and 6 per cent among respondents in North America.

The teaching that a chemistry master’s student in Germany has experienced “is very abstract and lacks references to why it is relevant in the larger picture”.

A psychology assistant professor in Austria notes that where teaching quality falls short, it is because “people are overloaded with work, forced into teaching as a part of their research job, or, in some places, such as the US, are not provided with enough compensation to make ends meet”.

A US physics professor puts it more succinctly: “None of us teaching has ever been trained how to teach well. And under the current circumstances, we do not have time to train.”

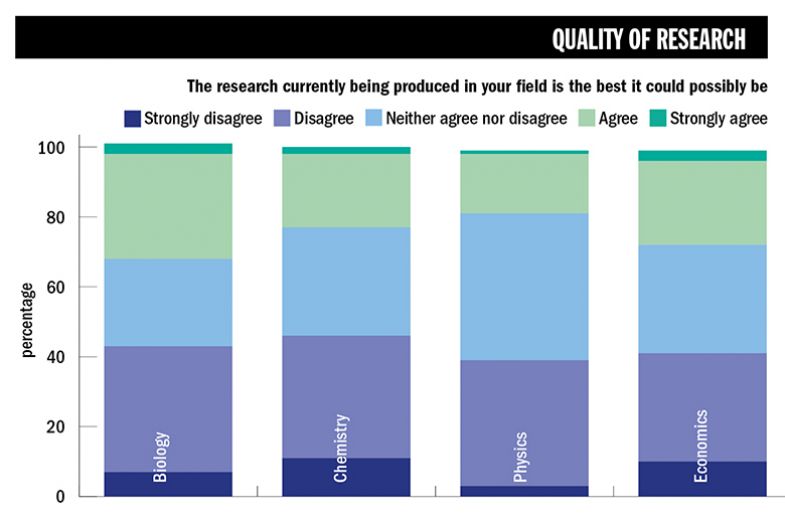

So what about research? Is that as good as it could be? Only marginally more respondents think so: 25 per cent, versus 44 per cent who disagree. Agreement rises to 37 per cent in Asia, but falls to 18 per cent in Europe and among physicists.

Many respondents make the point that, by definition, there is always room for improvement. But an informatics postdoc in Austria says there are specific problems: “The pace is way too fast, quality suffers and topics are very sensationalist. Few people care about reproducibility and impact.” And the public-sector biologist in Germany considers that “many old farts in the field block application of contemporary science”.

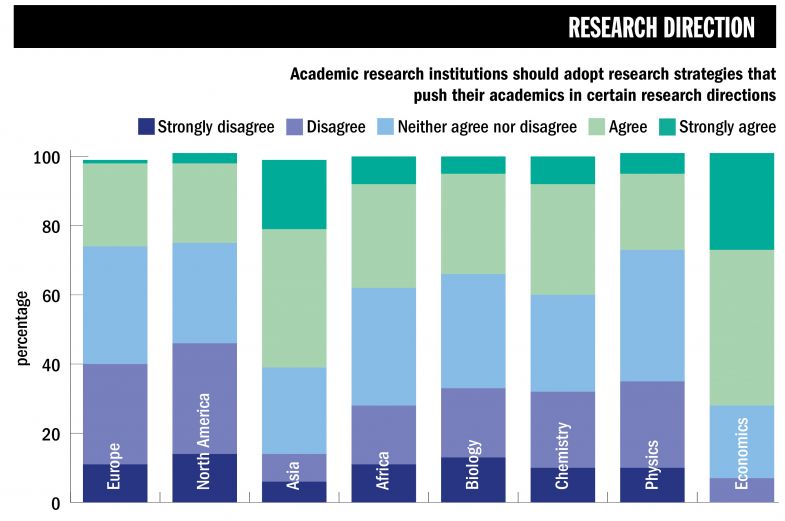

Some institutions, of course, actively embrace specific areas of contemporary science. But are institutions right to adopt research strategies that push their academics in certain directions? Opinion is split, with 36 per cent of respondents agreeing and 33 per cent disagreeing. Different sub-groups also give wildly different responses. In Asia, 60 per cent agree, and 72 per cent of economists do so, compared with just 27 per cent of physicists.

A US-based postdoc in biology says that institutional strategies “would truly be the end of academic research. Freedom of scientific pursuit is the foundation.” A Canada-based postdoc agrees that strategies “often lead to work that is derivative and uninspired...The best candle makers could have never discovered the light bulb.” And the assistant professor in Singapore says that “providing extra resources for one path is perhaps reasonable, but requiring someone to work on some area outside their expertise seems counterproductive. We are generally deeply specialised, so shifting areas is somewhat unfeasible over a short period.”

But a Germany-based research fellow believes that “each institution should establish priority research fields to seek excellence. This priority plan could be in agreement with national policies or actually work to help the government to establish nationwide research priorities.” And a researcher and lecturer in Mauritius sees institutional research strategies as “very important to improve the quality of research. Most of the time, academics carry out research and publish their research work just for the sake of promotion.”

A common view is expressed by a Singapore-based research fellow in chemistry: “It is important to set certain goals in research, but I don’t think research should be limited to those goals. Many breakthroughs came as a result of side projects.”

Respondents are slightly more positive about the idea of funders adopting research strategies that push academics in certain research directions, with 37 per cent agreeing that they should, against 33 per cent disagreeing. Agreement is highest in Asia (43 per cent) and at senior career levels. It is particularly low in physics (28 per cent) and biology (33 per cent).

Many of those who agree express caveats, suggesting that restricting funding to certain areas should only be done by small or private funders, or for translational research. But others believe that funders have a right to direct their money wherever they like. “If they want to support research in area X, that is their right as a philanthropist,” says the US administrator, a chemist.

“If you don’t like the direction of the funder, choose another one,” adds the public-sector biologist in Germany.

The other obvious institutional factor related to research success is job security. Asked whether they are concerned about theirs, 63 per cent agree, 29 per cent strongly, against 24 per cent who disagree. Agreement, unsurprisingly, is highest among those on insecure contracts. Women (68 per cent) are more likely than men (58 per cent) to be concerned, while Asia and Africa are the regions with the highest anxiety. By contrast, only 25 per cent of those in the private sector are concerned about job security.

“I love my job, but there’s just no reasonable way forward,” says a Sweden-based postdoc. “There’s so much personal sacrifice involved, and the chances of getting a non-fixed contract are so slim that it’s not worth it for me. It just seems impossible to be a scientist with a house, family and some sort of predictable future these days.”

The Austria-based assistant professor is relieved to be on the tenure track “but the climate is one of such competition that I do not yet feel secure”.

Others are worried not so much about their job security as about what its lack implies. The Netherlands-based chemistry postdoc “cannot apply for a grant because I don’t have an institutional guarantee of a contract long enough for it. I am looking for new universities that can give me that guarantee.”

But while a PhD student in Germany is worried about the security of his particular position, he is “certain I could find another one”. And, for the Singapore assistant professor, security “isn’t something I consider important”.

The pandemic

When the Covid-19 pandemic was at its height there were many predictions that it would change research topics and approaches. But has that transpired? Asked whether the pandemic has affected their research priorities, 49 per cent agree, 13 per cent strongly, while 31 per cent disagree. Predictably, agreement is highest (55 per cent) in biology. It is particularly high in Asia (57 per cent) and particularly low in Europe (40 per cent).

The chemistry research fellow in Singapore now prefers “low-risk research directions”, while the chemistry associate professor in Ghana has “become more interested in research in relation to the science advice/policy space”.

The Denmark-based postdoc was prompted to quit the “shitshow” of his former lab, whose boss “lied to authorities to get us back to the lab quicker because he believed Covid to be a hoax. I’m not going to risk my life for my career.”

Many scientists believe the pandemic proved the value of publishing early versions of papers on preprint servers, in order to speed up dissemination. But less than a third (31 per cent) of our respondents agree that all research should be published on a preprint server as soon as possible after it is completed; another third (33 per cent) disagree. Agreement is highest in biology (41 per cent) and lowest in economics (20 per cent).

Many respondents say that they were already convinced of the case for preprints prior to the pandemic – although not always for reasons of public information. “It ensures that I can claim that I was first to find something and people cannot scoop me as easily,” says a US-based postdoc in chemistry.

Others remain sceptical. “Either you have the peer review system or not. When is a scientific publication a scientific publication I can trust?” asks the public-sector biologist in Germany. And a Germany-based postdoc notes that “news establishments are confusing preprints with peer-reviewed articles. This should not be the case since preprints are very preliminary.”

A Sweden-based physics postdoc is more emphatic. “So much crap was published on these preprint sites during the pandemic…Of course, some things like RNA sequences need to be published right away in an emergency, but not the rest.”

Respondents are even more sceptical of another pandemic phenomenon: online teaching. Asked whether undergraduate science could be taught effectively entirely online, just 7 per cent of respondents agree, while 83 per cent disagree. A typical response comes from a Germany-based research fellow in chemistry: “The interaction of in-person classroom teaching can’t be replicated online. Also, the lab courses have to be in person, as practical skills need to be acquired.”

The chemistry master’s student in Germany did part of her undergraduate degree online: “I really lacked motivation and it was difficult to complete tasks when there was a disconnect between myself, peers and the professors,” she says.

A Canada-based private sector chemist taught an online undergraduate course during the pandemic that was a “disaster” due to such disconnections. However, she does see the value in "publishing short videos explaining concepts for students to watch before class, and instead using classroom time for problem-solving, discussions, and questions.”

What about online conferences? Asked whether they are preferable to in-person events, only 11 per cent agree, with agreement lowest at more senior career levels. But that doesn’t mean that respondents thought there was no place for online interaction. A Canada-based postdoc in chemistry thinks “there should always be an option to tune into a conference remotely for those who can’t travel to the location”, even if “organic and personal interactions are some of the most valuable aspects of conferences, and online events can never reproduce that”.

An Austria-based chemistry postdoc acknowledges the environmental case for online conferences, but her personal experience is that “networking is hardly possible in a setting online”.

Acknowledging all these points, the Singapore assistant professor would “like a world where most conferences are online. Ideally, I would like to travel, at most, one or two times a year.”

Impact

To many observers, the pandemic also underlined the importance of research impact. So is it academics’ responsibility to ensure their research has as much impact on the wider world as possible? Some 53 per cent of respondents agree, 13 per cent strongly. Only 20 per cent disagree. Agreement is markedly higher in Asia, although there are a few other significant variations by category.

Several respondents express scepticism about consciously chasing impact. “Science is about exploring the unknown. Sometimes it has impact, sometimes not, and sometimes it takes a really long time before we realise the impact. I think we should focus on doing our best to solve important problems and investigate interesting questions,” says a Sweden-based postdoc in physics.

The physics postdoc in Finland agrees – although if the research has a potential impact on the wider world, the “academic’s responsibility is to at least market it”, she says.

An Austria-based assistant professor in psychology believes it would be better to leave impact to dedicated professionals within institutions. “I think public outreach is really important, but it’s just not reasonable to expect academics to do this on top of everything else unless they specifically enjoy it,” she says.

All of that said, most respondents (73 per cent) agree that making a real-world impact is more important than publishing in a prestigious journal; only 8 per cent disagree. Agreement is lowest in biology (66 per cent) and higher in Africa (80 per cent) and among women (77 per cent) than men (71 per cent).

Yet several respondents see a connection between impact in publishing and in the real world. “By publishing in a prestigious journal, you then at least make sure that many people can be aware of what you’re doing,” says a Netherlands-based assistant professor in physics.

Several respondents caution that while impact is more important for them personally, it is not as important as publications for their careers. Asked specifically whether making a real-world impact brings as many career benefits as publishing in a prestigious journal, opinion is evenly split, with 36 per cent of respondents both agreeing and disagreeing. Agreement is lower in economics (23 per cent) and in Europe (26 per cent) and highest in Asia (55 per cent) – although a private-sector chief technology officer in Pakistan says that “in the academic culture in my country, the current faculty promotion and evaluation system counts only the number of publications meeting certain criteria. Unless the evaluation [criterion] has some metric for real-world impact, it will not bring career benefits.”

And a Switzerland-based biology postdoc says that while impact may benefit the careers of “established professors who [receive awards or become] government advisers, constantly in the news, their teams are working 150 per cent and still don’t get the publications necessary to land permanent jobs”.

“In the end, grants and career benefits mainly come with high-impact journal publications,” agrees a Sweden-based biology postdoc.

One important aspect of impact, beloved of governments, is commercialisation. But are universities and research institutions doing all they can to help academics explore the commercial potential of their research? Only 20 per cent of respondents think so, compared with 49 per cent who don’t. Agreement is higher in Asia (33 per cent) and Africa (27 per cent) than in Europe (18 per cent) and the US (19 per cent).

“There are some support services for commercialisation, but the real support, in terms of allowing time off to develop the business idea (without harming your career) or allowing people to combine business and research (without hugely overworking), does not exist,” says the physics postdoc in Finland.

According to the private-sector biologist in Germany, while universities do their best on commercialisation, they would do better to find “partners who can propagate the gains at a faster rate and create impact without losing time”.

One aspect of the push towards greater impact in recent years is an increasing emphasis on translational research. So do future research leaders believe that such research is as important as basic/frontier research? The answer is an overwhelming yes – 75 per cent of respondents agree with the proposition, 21 per cent strongly, versus only 6 per cent who disagree. The view is particularly strong in biology (91 per cent agree) and particularly weak in economics (48 per cent).

“Without translational research, basic research has no impact,” says a physics professor in the US. However, a Singapore-based assistant professor in economics counters that “translational research cannot exist without basic research. It is still useful, but it is generally of a lower impact.” And the public-sector biologist in Germany says universities should “explore new fields where no industry is interested in yet. The translational stuff is usually better done by industry.”

But, for a chemistry assistant professor in Italy, the dichotomy is false. “Society needs both basic and translational research. As soon as I establish my own group, I will develop different research lines with both goals,” she says.

The tension between translational and basic research arises in part over funding, of course. When the pot is finite, which should be prioritised? As things stand, is translational research underfunded compared with basic research? Only 16 per cent of respondents think that it is, compared with 34 per cent who disagree. But the picture varies in different countries.

The physics postdoc in Finland says that in the US, translational research is underfunded compared with frontier research, whereas in Finland the reverse applies. An associate professor of chemistry in Spain laments that “for many funding calls, it is mandatory to show that at the end of a project you will have a product for the market”. And the economics assistant professor in Singapore says it is “easier to sell a translational project to the government than basic research, as the benefit to the government is more clear and certain”.

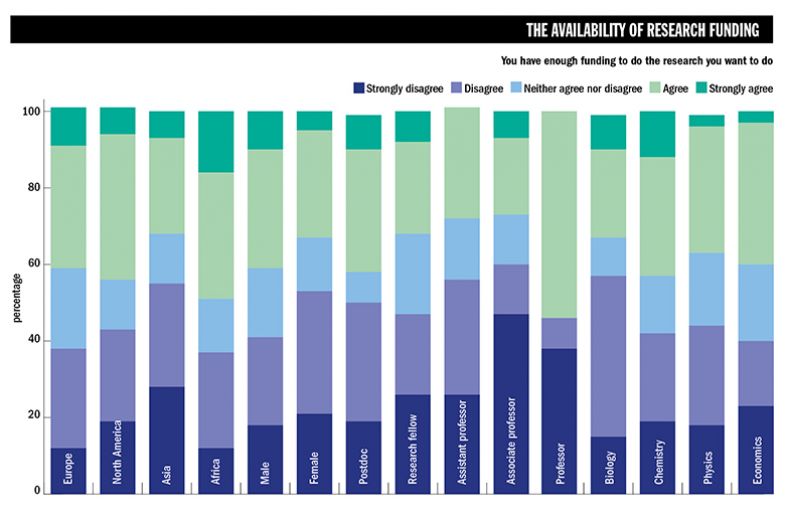

Funding more generally is clearly a bone of contention. Asked whether they have enough money to do the research they want to do, 46 per cent of respondents disagree, 19 per cent strongly, against 38 per cent who agree. Agreement is particularly low at mid-career levels. Women are much less likely than men to agree (34 per cent versus 42 per cent), and biologists (32 per cent) are less likely than other disciplines. Geographically, while respondents in Africa are, perhaps surprisingly, more positive than other regions (49 per cent), Asia is much less positive (33 per cent).

“Research work depends on the allotted funding, says a chemistry assistant professor in Bangladesh. “We are always fixing a suitable budget and then working accordingly.”

“The government of India invests dismally in research,” adds an assistant professor in chemistry in that country.

Even where funding is more abundant, problems persist; the Singapore economics assistant professor has enough money but not enough “ability to allocate the funds to what is actually needed”.

Team and interdisciplinary research

Many observers predict that the future of science lies in larger teams, many of them interdisciplinary. But are large teams more likely to make important discoveries than smaller teams? Only 31 per cent of respondents agree that they are, against 40 per cent who disagree. Negativity is, surprisingly, particularly high in physics, the field most associated with big science (26 per cent, against 44 per cent), although it is even higher in economics (14 per cent, against 59 per cent).

A common observation is that the need for large teams depends on the research question. But other factors are mentioned too. For a Netherlands-based assistant professor in chemistry, scientific success is “a numbers game. There are also only so many good students even within top institutes. So one needs a critical group size to have multiple successful research lines.”

A Germany-based PhD student in chemistry believes that “small teams allow for better communication and exchange of ideas. In big teams, the ideas have already been had and they’re just putting them into practice.”

But does working in large teams actually stifle scientific creativity? Opinion is fairly evenly split, with 31 per cent agreeing and 28 per cent disagreeing.

“It depends on how the large teams are organised and managed,” says a private-sector chemist in Canada. “I’ve seen both extremes. On the one hand, a student in a large team risks being simply a cog in a larger machine, repeating a single calculation or procedure. On the other hand, if the large team includes researchers of diverse backgrounds, given room to brainstorm and collaborate across multiple disciplines, backgrounds and techniques, then the environment is ideal for nurturing creativity.”

So is engaging with researchers from beyond your immediate field likely to improve your research? Respondents overwhelmingly believe so, with 91 per cent agreeing and just 1 per cent disagreeing, with similar figures recorded across the disciplines.

Engagement with other fields stimulates researchers to “look at a problem from a totally different angle”, says the private-sector biologist in Kenya – although a physics postdoc in Sweden notes that fruitful collaborations take time to establish.

What about non-academic impact: is this likely to be higher in interdisciplinary collaborations? Again, respondents strongly believe so, with 69 per cent agreeing and only 6 per cent disagreeing. Economists are particularly positive, with 87 per cent agreeing and none disagreeing; biologists are less positive, although 64 per cent still agree and only 4 per cent disagree.

However, the psychology assistant professor in Austria notes that it depends on the research question. An interdisciplinary approach “can address a question that is already burning in the general public’s mind or it can address a question that is extremely obscure and only becomes more obscure by bringing two disciplines together”, she says.

If interdisciplinarity is so positive for research quality and impact, are academic institutions doing enough to encourage and reward it? Only 24 per cent of respondents believe so, against 41 per cent who disagree. Respondents in Asia are much more likely to agree (40 per cent) than those in Europe (19 per cent), while economists (14 per cent) and biologists (20 per cent) are less likely than other fields to agree.

A common remark is that while institutions pay lip service to interdisciplinarity’s importance, they don’t offer sufficient active support. “There are many ‘initiatives’ to promote it, but interdisciplinarity takes a lot more energy, a lot more time, is more difficult to perform and to publish. For example, virology lab rules are made for keeping everything in the virology lab. It is difficult to bring samples to other institutions,” says a postdoc in Sweden.

Moreover, “many institutions adhere to fairly rigid divisions between disciplines. While it might be easier to do interdisciplinary work within a department, it’s harder across multiple departments,” says a chemistry postdoc in Canada.

One frequently cited reason for the perceived difficulty of publishing interdisciplinary research is that its quality is harder to assess. Our respondents largely concur, with only 26 per cent agreeing that good interdisciplinary work is as easy to identify as good single-disciplinary work, against 43 per cent who disagree. Agreement is particularly low (17 per cent) among economists.

“The results of interdisciplinary research certainly need to be evaluated by interdisciplinary experts, but interdisciplinary experts are not so easy to identify,” says a physics doctoral student in China.

However, a physics PhD student in Germany notes that it is “usually easier to identify good interdisciplinary work than to identify good single-disciplinary work if one is not working in the same field”.

Internationalisation

A final plank for research success is often purported to be international experience and networks. Our respondents emphatically concur, with 88 per cent agreeing that international networks have had a crucial impact on their research and career. Only 3 per cent disagree. Agreement rises to 92 per cent in Asia.

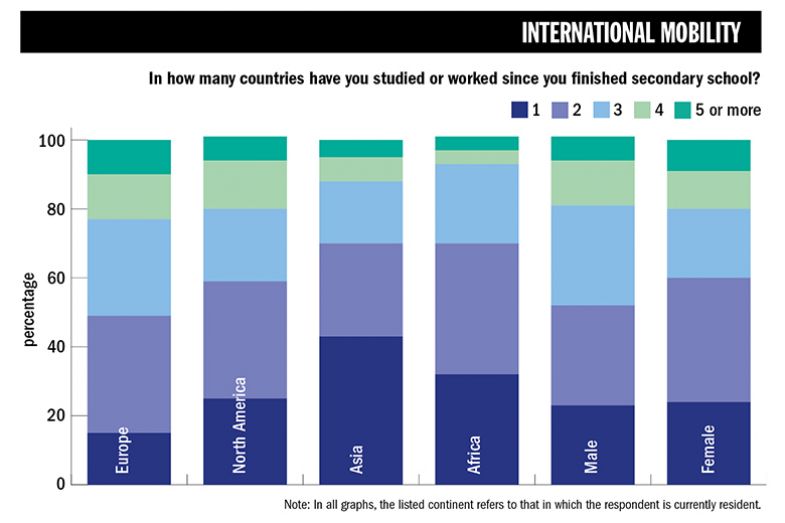

Yet, somewhat paradoxically, respondents in Asia are also much more likely to have studied or worked in only one country since leaving secondary school: 43 per cent have done so, compared with 32 per cent in Africa, 25 per cent in North America and just 15 per cent in Europe. The last group are the most mobile, with 51 per cent having studied or worked in three or more countries, against only 30 per cent of people in Asia. More men (49 per cent) than women (40 per cent) have worked or studied in three or more countries.

Not everyone embraces international mobility willingly. A female chemistry research fellow in Portugal says that while pursuing international positions was important in the past, when there was “little equipment” at many institutions, “if I, at my university, have everything I need, why do I need to go away from home and my family and compromise my work-life balance?”

A chemistry postdoc in the Netherlands finds “national networks stronger and more powerful” than international ones. On the other hand, an economics research fellow in Colombia “can’t stress enough how useful it has been to participate in international in-person and online conferences. It has given me the opportunity to share my research, receive great feedback from various backgrounds and fields, and even get to know co-authors,” he says.

In a world of rising tensions, of course, the politics of international collaboration is becoming trickier. But would respondents avoid a collaboration with a researcher from a country whose government they disapproved of? Only 16 per cent agree that they would, against 59 per cent who would not. Those at junior career levels and in North America are particularly unlikely.

“For sure, I would think about it. But I’m aware that researchers are not politicians and their government many times does not represent them,” says an associate professor of chemistry in Spain. A doctoral student in biochemistry in Mexico adds that “there will always be disagreements between nations, but I believe that the scientific field is an area free of these questions. People collaborate out of pleasure and passion for their work.”

The Kenyan private-sector scientist is also unconcerned by politics, provided her collaborator has “individual integrity”.

But an assistant professor in the Netherlands is torn: “On one hand, I think science should be free of politics, but, on the other hand, it is almost impossible to separate,” he says. And a Denmark-based postdoc says that “science cannot be unpolitical…You cannot punish individuals for where they were born, but definitely for their opinions.”

Several respondents say they would only consider cutting ties if the project was funded by the offending government, if it stood to benefit that government in some way, or if the people involved in the collaboration were connected to the regime.

But not everyone agrees that such distinctions can always hold. “This spring, I had to cancel a collaborative project with a fine Russian PI due to the Russian attack [on] Ukraine,” says the physics postdoc in Finland. The PI was strongly against the attack and we both agreed that stopping the collaboration is one of the small actions we can readily take to protest against the Russian government.”

Interestingly, respondents are more likely to regard it as legitimate for governments themselves to restrict researchers’ collaborations with certain countries for security, commercial or political reasons. Overall, 28 per cent agree that this can be appropriate, although 48 per cent still disagree. Respondents in Europe are more likely to agree (34 per cent), while those in Asia are least likely (21 per cent).

But many respondents regard some reasons for restrictions as more legitimate than others. “For humanitarian reasons: yes. For security reasons: maybe. For commercial or political reasons: no,” says a Germany-based chemistry postdoc. A Canadian private-sector biologist, on the other hand, sees restrictions as especially valid “where there is evidence that it threatens security or protection of intellectual property”. And a Germany-based research fellow in chemistry considers it legitimate for governments to shut down institutional-level collaborations, but not researcher-to-researcher ones. But a Germany-based postdoc in biophysical chemistry thinks any government-imposed restrictions on collaboration would be “astonishingly stupid and immoral”.

The question of whether the pursuit of research success should bow to wider ethical and commercial considerations is clearly one that is not going away any time soon.

THE research success survey 2022 results in full

|

To what extent do you agree with the following propositions? |

Strongly disagree (%) |

Disagree (%) |

Neither agree nor disagree (%) |

Agree (%) |

Strongly agree (%) |

|

All young people, regardless of background, have an equal chance to have a successful research career. |

24 |

42 |

10 |

11 |

13 |

|

Universities and research institutes typically appoint and promote the most qualified candidates. |

6 |

25 |

31 |

33 |

4 |

|

Researchers from underrepresented groups should be preferentially recruited by universities and research organisations. |

6 |

17 |

37 |

34 |

6 |

|

The involvement of people from a range of backgrounds improves the quality of science and research. |

1 |

2 |

8 |

41 |

49 |

|

Institutional reputation affects the way research is judged by journals, grant panels and others. |

1 |

2 |

7 |

46 |

44 |

|

Institutional reputation influenced your choice of your current or most recent university or research institute. |

4 |

14 |

15 |

50 |

17 |

|

Peer review is the fairest system to allocate journal space and grants. |

6 |

16 |

34 |

39 |

6 |

|

In your experience, the process of peer review generally improves papers. |

0 |

5 |

17 |

62 |

15 |

|

Mentoring is an important factor for research success. |

1 |

1 |

2 |

35 |

61 |

|

In your most recent academic position, you have/had the level of mentoring you need to be successful. |

6 |

18 |

21 |

40 |

16 |

|

Academic institutions support pursuing an academic career while having obligations related to family/childcare. |

11 |

32 |

31 |

19 |

6 |

|

A culture of overwork in your field negatively affects work-life balance. |

0 |

3 |

14 |

47 |

35 |

|

Universities and research institutes do everything they reasonably can to support academic careers. |

12 |

39 |

31 |

15 |

2 |

|

Academic research institutions should adopt research strategies that push their academics in certain research directions. |

10 |

23 |

31 |

29 |

7 |

|

University academics should be required to be both good researchers and good teachers. |

4 |

15 |

12 |

43 |

26 |

|

You are concerned about your job security. |

7 |

17 |

13 |

34 |

29 |

|

The pandemic has affected your research priorities. |

6 |

25 |

20 |

36 |

13 |

|

The pandemic has convinced you that all research should be published on a preprint server as soon as possible after it is completed. |

8 |

26 |

35 |

22 |

10 |

|

Undergraduate science could be taught effectively entirely online. |

40 |

43 |

11 |

6 |

1 |

|

Online conferences are preferable to in-person events. |

33 |

36 |

19 |

8 |

3 |

|

It is academics’ responsibility to ensure their research has as much impact on the wider world as possible. |

4 |

16 |

27 |

40 |

13 |

|

Making a real-world impact is more important than publishing in a prestigious journal. |

2 |

6 |

18 |

42 |

31 |

|

Making a real-world impact brings as many career benefits as publishing in a prestigious journal. |

10 |

27 |

28 |

23 |

13 |

|

Universities and research institutions are doing all they can to help academics explore the commercial potential of their research. |

12 |

38 |

31 |

18 |

2 |

|

Translational research is just as important as basic/frontier research. |

1 |

6 |

18 |

54 |

21 |

|

Translational research is underfunded compared with basic research. |

7 |

27 |

50 |

10 |

6 |

|

Large teams are more likely to make important discoveries than smaller teams. |

8 |

31 |

30 |

20 |

11 |

|

Working in large teams stifles scientific creativity. |

4 |

24 |

41 |

26 |

6 |

|

Engaging with researchers from beyond your immediate field is likely to improve your research. |

0 |

1 |

7 |

56 |

35 |

|

Engaging with researchers from beyond your immediate field is likely to increase your work’s non-academic impact. |

0 |

6 |

25 |

52 |

17 |

|

Academic institutions are doing enough to encourage and reward interdisciplinary work. |

6 |

35 |

35 |

22 |

2 |

|

Good interdisciplinary work is as easy to identify as good single-disciplinary work. |

6 |

38 |

31 |

23 |

4 |

|

International networks have a crucial impact on your research and career. |

1 |

3 |

9 |

42 |

46 |

|

You would avoid a collaboration with a researcher from a country whose government you disapprove of. |

18 |

41 |

25 |

13 |

4 |

|

It is appropriate for governments to restrict collaborations with certain countries, for security, commercial or political reasons. |

21 |

27 |

24 |

23 |

5 |

|

You have enough funding to do the research you want to do. |

19 |

27 |

16 |

30 |

8 |

|

Funders are right to adopt research strategies that push academics in certain research directions. |

8 |

25 |

30 |

33 |

4 |

|

The research currently being produced in your field is the best it could possibly be. |

8 |

35 |

32 |

22 |

2 |

|

The teaching currently being delivered in your field is the best it could possibly be. |

13 |

41 |

31 |

13 |

2 |

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login